The Monopoly of Credit

By C H Douglas

Chapter Three

Government by Finance

THE modern State is an unlimited liability corporation, of which the citizens are the workersand guarantors, and the financial system the beneficiary. To see that this is a plain statementof fact, it is, I think, only necessary to understand the nature and the origin of money.Money is essentially an order system. It has been defined by Professor Walker* as "anymedium no matter of what it is made or why people want it, no one will refuse in exchangefor his goods." That is to say, a given denomination of money may at any time be exchangedfor any article bearing a price figure corresponding to this denomination of money, and it is asimple extension of this proposition to say that the power of creating money is a guarantee ofthe power of acquiring goods or services to a total proportion of the whole stock of goods andservices equal to the percentage of existing money which can be created.

*“Money, Trade and Industry,” p.6.

It is now fairly well understood that the power of creating money is for all practical purposes confined to the financial system, which is mainly under the control of the banks. Mr. McKenna, Chairman of the Midland Bank, put the matter shortly in his annual addresses to the shareholders of that institution by remarking that "every bank loan and every purchase of securities by a bank creates a deposit, and the withdrawal of every bank loan, and the sale of securities by a bank, destroys a deposit."* It may be noted in passing, that this is the same thing as saying that a bank acquires securities for nothing, in the same way that a central bank, such as the Bank of England, may be said to acquire gold for nothing. In each case, of course, the institution concerned writes a draft upon itself for the sum involved, and the

general public honours the draft by being willing to provide goods and services in exchange for it.

*Annual General Meeting, Midland Bank, January 25th, 1924

Since the mechanism by which money is created by banks is not generally understood, and the subject is obviously of the highest importance, it may be well to repeat here an explanation of the matter which I have given elsewhere.

Imagine a new bank to be started—its so-called capital is immaterial. Ten depositors each deposit £100 in bank-notes with this bank. Its liabilities to the public are now £1,000. These ten depositors have business with each other and find it more convenient in many cases to write notes (cheques) to the banker, instructing him to adjust their several accounts in accordance with these business transactions, rather than to draw out cash and pay it over personally. After a little while, the banker notes that only about 10 per cent of his business is done in cash (in England it is only 0.7 of 1 per cent), the rest being merely bookkeeping. At this point depositor No. 10, who is a manufacturer, receives a large order for his product. Before he can deliver, he realises that he will have to pay out, in wages, salaries, and other expenses, considerably more "money" than he has at command. In this difficulty he consults his banker, who, having in mind the situation just outlined, agrees to allow him to draw from his account not merely his own £100 but an "overdraft" of £100, making £200 in all, in consideration of repayment in, say, three months, of £102. This overdraft of £100 is a credit to the account of depositor No. 10, who can now draw £200.

The banker's liabilities to the public are now £1,100; none of the original depositors have had their credits of £100 each reduced by the transaction, nor were they consulted in regard to it; and it is absolutely correct to say that £100 of new money has been created by a stroke of the banker's pen.

Depositor No. 10 having happily obtained his overdraft, pays it out to his employees in wages and salaries. These wages and salaries, together with the banker's interest, all go into costs. All costs go into the price the public pays for its goods, and consequently, when depositor No. 10 repays his banker with £102 obtained from the public in exchange for his goods, and the banker after placing £2, originally created by himself, to his profit and loss account, sets the £100 received against the phantom credit previously created, and cancels both of them, there are £100 worth more goods in the world which are immobilised— of which no one, not even the banker, except potentially, has the money equivalent. A short mathematical proof of this process is given in Appendix I.

Leaving for the moment certain serious difficulties of a technical nature which arise out of this process, it is, I think, desirable to examine its fundamental meaning, and a clearer idea of this may, perhaps, be obtained by considering, for example, Great Britain as a commercial undertaking and producing a balance sheet. Speaking generally, it is true to say that in any undertaking its potentialities are its assets, and the actual or contingent calls upon these potentialities are its liabilities. The subjoined balance sheet is constructed in accordance with this conception.

| Assets | Liabilities |

|

Human Potential (Population, Education, Morale) Policy Organisation Natural Resources Developed Power Plant (Railways, Buildings, Tools, etc.) Goodwill (Tradition, reputation, etc.) Work in Progress Consumable Goods |

National Debt Bankers (Potential creators of effective demand). Insurance Companies (Mortgage and Bond Holders). Cash at call Taxation for Public Services |

Page 1

An examination of a document constructed on these principles will at once reveal the fact that it differs in certain important particulars from any official or public account. The liabilities are not defined, the fixed assets appear on the opposite side of the account to the money assets, and the two sides do not balance, and cannot, in fact, be made to balance. In short, the financial system is seen to be, as it is, in opposition to every other interest.

These considerations inevitably involve an examination and definition of the fundamental basis of credit. Credit obviously cannot be based upon a liability, nor can the collective interests, which we call national, be so opposed to the interests of the individuals composing them that the nearer the nation approaches bankruptcy, the richer become its constituent parts. If there were no other arguments, and there are many, I think this would be sufficient to dispose of the primary contention of the existing banking and financial system, which bases credit upon currency, and in the case of Gold Standard countries, in theory, bases currency upon gold.

Real credit may be defined as the rate at which goods and services can be delivered as, when, and where required. Financial credit may similarly be defined as the rate at which money can be delivered, as, when, and where required. The inclusion in both definitions of the word "rate" is, of course, important.

An aspect of this matter worthy of attention is the convention by which the liability of the community becomes the asset of the individual. If we take the National Debt of Great Britain as being in round figures £8,000,000,000 it would be, I suppose, admitted without much hesitation that Great Britain as a community was poorer by the amount of this debt. On the other hand, each holder of War Loan would regard himself as being richer by the amount of the War Loan which he holds. Both of these statements are, of course, true, and if the Debt were held equally by individuals it would simply represent a licence to work, using National Real Capital. But the debt having been originally created by the same process which enables the banking system to create money, and so far as it is in the hands of the public, exchanging this debt so created for purchasing power already in existence, it is a transfer of purchasing

power from the public to the banks. It is probable that the amount of War Debt actually owned by individuals has never exceeded 20 per cent of the total debt created, the remaining 80 per cent being either in the actual ownership, or under lien to banks and insurance companies, the net result of the complete process being the transfer to the financial system of 4/5 of the purchasing power represented by £8,000,000,000.

It is no answer to this accusation to say that financial institutions are owned by individuals. A financial institution can operate only through financial investment or manipulation, and these, as it is hoped to make clear, are in themselves the fundamental cause of the world's difficulties.

Page 2

A student of the preceding pages will have grasped the important fact that money is not made by industry. Neither is it made by agriculture, or by any manufacturing progress. The farmer who grows a ton of potatoes does not grow the money whereby the ton of potatoes may be bought, and if he is fortunate enough to sell them, he merely gets money which someone else had previously.

Purchasing power, therefore, is not, as might be gathered from the current discussions on the subject, an emanation from the production of real commodities or services much like the scent from a rose, but on the contrary, is produced by an entirely distinct process, that is to say, the banking system. Bearing this in mind, we can understand that it is impossible for a closed community to operate continuously on the profit system, if the amount of money inside this community is not increased, even though the amount of goods and services available are not increased. This obvious but commonly overlooked fact forms the justification, if any, for the idea on which Socialist policy for the past hundred years has been

based—that the poor are poor because the rich are rich. If a number of persons continue to sell articles at a greater price than that paid for them, they must eventually come into possession of all the money in the community, and the only flaw in such a state of affairs would be that it would be self-destructive, since in a comparatively short period of time a small section of the community would own all the money, and therefore the remainder of the community would be unable to pay, and production and sale would stop. This process probably contributed largely to the rapid accumulation of wealth in the hands of the

entrepreneur at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the limited extent to which the benefits of industrial progress were passed on to the general population; but the profit-making system is certainly not to any great extent responsible for the present situation, since profits have ceased to form an outstanding feature of business. It is an extraordinary feature of the controversy that they are attacked as immoral as well as undesirable. It has never been clear to me why any man in any position of life should be expected to perform any action whatever which was not in some sense of the word profitable to him, and there is more than a suspicion that the attack upon profits can ultimately be traced to a fear of the economic security offered by this type of remuneration, as compared with that of the wage and salary.

The factor which is probably at the root of the problem is at once more complex and more subtle, and has during the past few years been a matter of acrimonious controversy. On its physical or realistic side it is intimately connected with the replacement of human labour by machine labour.

The physical effects of this replacement are not difficult to apprehend. If one unit of human labour with the aid of mechanical power and machinery will produce ten times as much as the same unit working without such aids, it is obvious that there will either be ten times as much production or only one-tenth the amount of labour will be required.

The productivity of a unit of human labour has increased somewhat irregularly over the whole field of production. In some cases the increase in a hundred years has amounted to thousands per cent, in some cases the increase of output per unit has been much less. It is, however, broadly true to say that general economic production, which may be defined as the conversion of existing materials into a form suitable for human use, is proportional to the rate at which energy of any description is used in the process, and this line of attack is probably closer to reality than any method in which financial units are employed.

On this basis it is safe to say that one unit of human labour can on the average produce at least forty times as much as was the case up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. The following examples are some indication of the progress made in the past few years alone.

The rate of production of pig-iron is three times as great per man employed as it was in 1914. A workman using automatic machines can make 4,000 glass bottles as quickly as he could have made 100 by hand twenty-five years ago. In 1919 the index of factory output (based upon 1914 as 100) was 146, and the index of factory employment was 129. By 1927 output had risen to 170, but employment had sunk to 115. In 1928 American farmers were using 45,000 harvesting and threshing machines, and with them had displaced 130,000 farm hands. In automobiles, output per man has increased to 310 per cent, an increase of 210 per cent.

When we approach the question of distribution, however, we find a remarkable discrepancy. Professor Paul H. Douglas states in his examination of the problem that, in the first quarter of the twentieth century, real wages increased 30 per cent, productivity per employee increased by 54 per cent. In 1923 production increased 38 per cent, but consumption by wage-earners 32 per cent. In 1925 production increased 54 per cent, but consumption only 30 per cent. These latter figures compare with 1913 as a basis.

Page 3

Eliminating the pseudo-moral complications commonly introduced into this aspect of the subject, it is clear that certain consequences were bound to ensue. Either the requirements of the population must increase at the rate at which the capacity for production increases, and at the same time the financial mechanism must be adjusted to provide for the distribution of the production, or a decreasing number of persons would be required in production. Unless the wages of this decreasing number of individuals collectively rises to the amount which, previously distributed to a larger number of workers, would buy the still greater production, either costs and prices must fall, or an increasing proportion of the goods must be unsold to the persons who produced them. Certain consequences, readily understood if it be

remembered that wages, costs, and purchasing power are only different aspects of the same thing, accompany a continuous fall in costs under the existing financial system, and a fall of prices, while off-setting these consequences to some extent, involves the entrepreneur in a loss on the whole of his stocks, a loss which he is not usually willing, or indeed able, to take.

The first aspect of this complex situation which demands attention is the financing of capital production by means of the reinvestment of savings, which, it should be noticed, is the method commonly stated to be the proper method. It is doubtful whether more than an insignificant proportion of financing is done in this way, the greater part coming from new credits supplied by banks and insurance companies in return for debentures, but it forms the smoke-screen which conceals the fact that public issues are in the main acquired by financial institutions through the medium of drafts upon themselves. The growth of insurance has no doubt been a considerable factor in accelerating the process. If we consider the case of a workman earning, let us say, £5 per week, who saves £1 of this and at the end of a hundred weeks subscribes for shares in a new manufacturing company, the effect is not hard to trace. The original £5 per week was wages paid to the workman, and these wages were, by the orthodox costing system, debited to the cost of the articles produced by his employer. Eventually, due to his saving, these articles cannot be sold, as a simple arithmetical proposition shows, since he has taken 20 per cent of the necessary purchasing power off the market. His investment of this 20 per cent we may assume results in the manufacture of machinery in which his £100 again appears as wages. Assuming that no physical

deterioration has taken place, or that the goods have not been exported, the 20 per cent deficiency in the first cycle of production has now been restored, and the original goods could be bought. But the machinery which has been made in the second cycle of production is now a charge on further production for which no purchasing power whatever exists. This proposition may be generalised as follows: Where any payment in money appears twice or more in series production, then the ultimate price of the product is increased by the amount of that payment multiplied by the number of times of its appearance, without any equivalent increase of purchasing power.

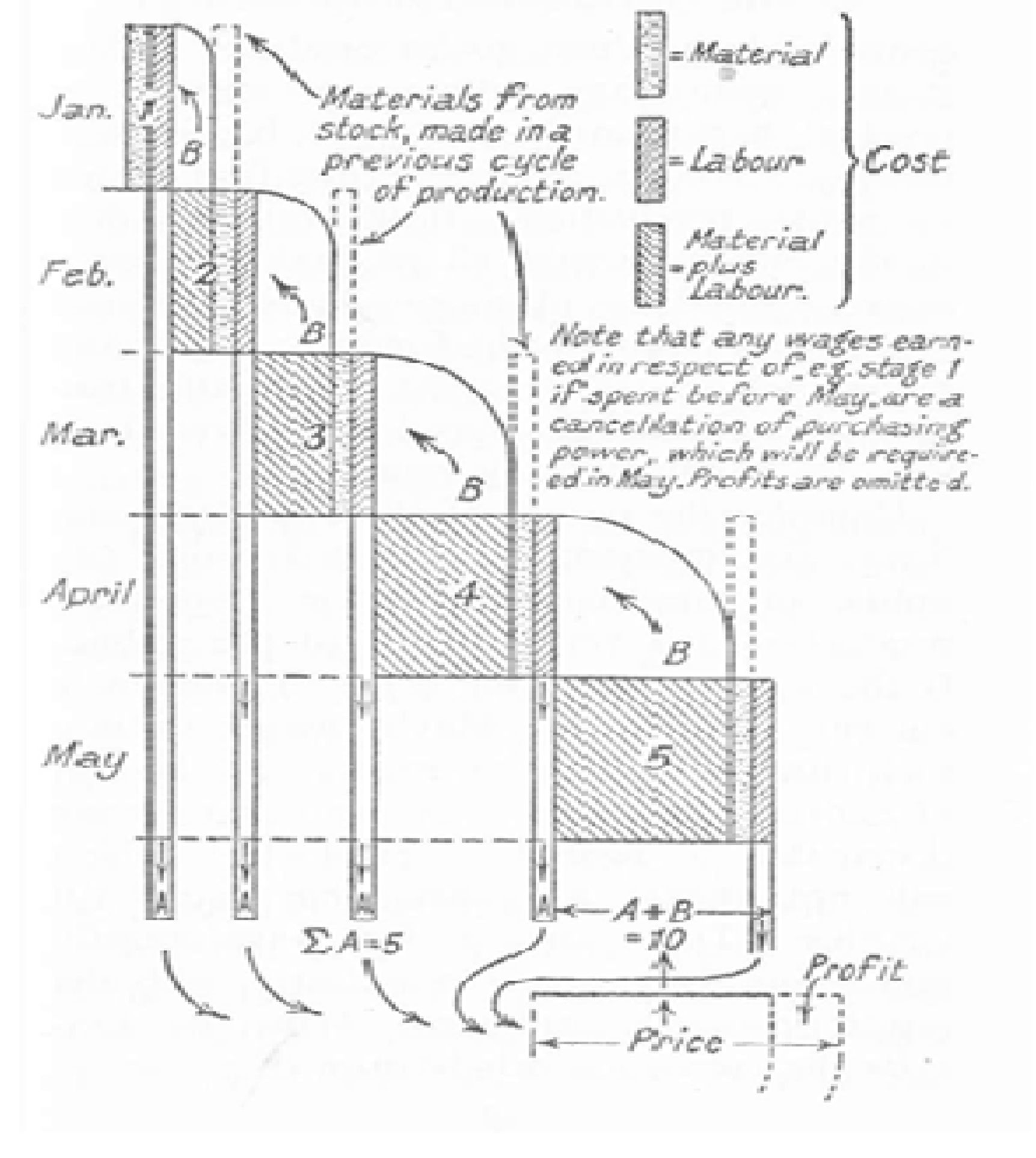

With this fundamental proposition in mind we are in a position to take a more generalised view of the defect in the price system which is concerned with the double circuit of money in industry, and which has become known as the A plus B theorem. The statement of this is as follows: In any manufacturing undertaking the payments made may be divided into two groups: Group A: Payments made to individuals as wages, salaries, and dividends; Group B: Payments made to other organisations for raw materials, bank charges, and other external costs. The rate of distribution of purchasing power to individuals is represented by A, but since all payments go into prices, the rate of generation of prices cannot be less than A plus B. Since A will not purchase A plus B, a proportion of the product at least equivalent to B must be distributed by a form of purchasing power which is not comprised in the description grouped under A.

Now the first objection which is commonly raised to this statement is that the payments in wages which are made to the public for intermediate products which the public does not want to buy and could not use, when added together, make up the necessary sum to balance the B payments, so that the population can buy all the consumable products. But an examination of the diagram on the next page will show that this is not a satisfactory explanation. If we imagine consumable products to be produced in five stages, each stage taking one month, a product begun in January will be finished in May. We can regard the first four stages as capital production. It is irrelevant that in the modern world all of these

five processes are taking place simultaneously and that the product may be found in any of the five stages at any moment. It is still true that you cannot bake bread with corn which you are simultaneously grinding.

Consider the nature of these B payments. They are repayments collected from the public of purchasing power in respect of production not yet delivered to the public. If the wageearners in process "1" use their current month's, i.e. May's, wages to buy their share of one current month's production of consumable goods, they are using money distributed in respect of production which will not appear as consumable goods till October. They are in fact involuntarily reinvesting their money in industry, with the result previously explained. When we consider the increasing sub-division of process— and in "process" we may include the using of machine-tools, buildings, and the general plant of the country—it will readily be understood that this period shown as five months in the diagram may easily cover many years.

Page 3

As the economic system may be said to depend upon this matter, it is essential that clear understanding of it should be obtained.

Let us imagine a capitalist to own a certain piece of land, on which is a house, anbuilding containing the necessary machinery for preparing, spinning and weaving linen, and that the land is capable of growing in addition to flax, all the food necessary to maintain a man. Let us further imagine that the capitalist in the first place allows a man to live free of all payment in the house and to have the use of all the foodstuffs that he grows on condition that he also grows, spins and weaves a certain amount of linen for the capitalist. Let us further imagine that after a time this arrangement is altered by the payment to the man of 1 pound a week for the work on the linen business, but that this 1 pound is taken back each week as rent for house and payment for the foodstuffs he might not have been able to obtain had not the knowledge and organisation of the capitalist brought together housing, flax, food, and machinery. In other words, the problem disclosed is not a moral problem, it is an arithmetical problem.

Let us now imagine that half of the employee's time is devoted to making a machine which will do all the work of preparing and manufacturing linen, and that the manufacture of this machine takes twelve weeks. We may therefore say that the machine costs £6, the total value of the production of machine and flax being still £1 per week. At the end of this period the machine is substituted for the man, the machine being driven, we suppose, by the burning of the food which was previously consumed by the man, and the machine being housed in the house previously occupied by the man, and being automatic. The capitalist will be justified in saying that the cost of the operation of the machine is £1 per week as before, and if there is any wear, he will also be justified in allocating the cost of this wear to the cost of the linen. It should be noticed, however, that he will now not distribute any money at all, since it is obviously no use offering a £1 note a week to a machine. He will merely allocate this cost, and once again the allocation will be perfectly fair and proper, but no one will be able to pay the price, because no one has received any money.

In the modern industrial system, this process can be identified easily in the form of machine charges. For instance, a modern stamping plant may require to add 600 per cent to its labour charges to cover its machine charges, this sum not being in any true sense profit. In such a case, for every £1 expended in a given period in wages, £6, making £7 in all, would be carried forward into prices. Although this is an extreme case, the constant, and in one sense desirable, tendency is for direct charges to decrease and for indirect charges to increase as a result of the replacement of human labour by machinery. There is no difference between a plant charge of this nature and a similar sum repaid as a "B" payment. The essential point is that when a given sum of money leaves the consumer on its journey back to the point of origin in the bank it is on its way to extinction. If that extinction takes place before the extinction of the price value created during its journey from the bank, then each such operation produces a corresponding disequilibrium between money and prices. For these causes and others of a similar character, it seems to me quite beyond argument that the production of such a quantity of intermediate products, including plant, machinery, buildings, and so forth, as is physically necessary to maintain a given quantity of consumable products, will not provide a distribution of purchasing power sufficient to buy these consumable products. This would be true even if prices and costs were identical. But since prices can and do rise much above costs, additional purchasing power from intermediate production is rapidly absorbed.

To say that at some time or other the money has been distributed is in the nature of a general assertion which does not bear upon the specific fact. The mill will never grind with the water that has passed, and unless it can be shown, as it certainly cannot be shown, that all these sums distributed in respect of the production of intermediate products are actually saved up, not in the form of securities, but in the form of actual purchasing power, we are obliged to assume what I believe to be true, that the rate of flow of purchasing power derived from the normal and theoretical operation of the existing price system is always less than that of the generation of prices within the same period of time.

There is another method of regarding this matter which is helpful to the grasp of an admittedly difficult subject. Suppose that the wages, salaries, and dividends distributed were exactly sufficient to buy the new production on sale at any moment and did so buy it, i.e. Let us suppose that the financial system worked as it is supposed to work. Obviously numbers of things would be bought, such as houses, furniture, etc., which would have a considerable life. But ex hypothesi the sale between consumers (as distinguished from sales from producer to consumer) of these would be impossible—they would have no money, since at the moment of transfer of the goods from the producing to the consuming system their money value would have disappeared on its journey back to the bank, to finance a fresh cycle of production.

Sales between consumers are an important though frequently overlooked factor in distribution, and require that the money value of "second-hand" goods shall be in existence until the goods have physically disappeared.

It may, with reason, be asked how if this be so, is it that in fact consumable products are sold at all? The answer to this is again complex, but the main forms in which assistance is given to the defective purchasing power of the population (although that assistance is much less than is required to enable the production system fully to be drawn upon) are the redistribution of money through the social services such as the so-called dole, the use of money received from the sale of exports, from foreign investments and from invisible exports such as shipping, redistributed through the medium of taxation, the distribution of bank loans (advanced on mortgage, debentures, etc.), in wages for excessive capital production, and the selling of goods below cost through the agency of bankruptcies, forced sales, and actual destruction. These latter three are a direct discouragement to production, and in fact represent a subsidy in aid of prices from private sources, a conception which it is desirable to bear in mind in considering remedies, in view of the fact that, so far from this subsidy raising prices, it comes into operation only by the lowering of prices.

It is also clear that the longer the average period over which money is collected in respect of the creation and destruction of a capital asset (which corresponds to the "life" of an asset), and the shorter the average period over which money is collected for day-to-day living on the part of the community (which corresponds to the "life" of consumable goods), the greater will be the discrepancy between purchasing power and prices.

The former period is the average time in years (N2) taken to make and wear out a capital asset; it is the time covered by the production and destruction of a cost. Obviously, such a period will vary greatly according to the nature of the asset, but a fair and usual average is twenty years.

The latter period is the average time in years (N1) during which the money at the disposal of the community (total income) circulates from industry to the consumer and back again. "In Great Britain, for instance, the deposits in the Joint Stock Banks are roughly £2,000,000,000. In rough figures, the annual clearings of the clearing banks amount to £40,000,000,000. It seems obvious that the £2,000,000,000 of deposits must circulate twenty times in a year to produce these clearing-house figures, and that therefore the average rate of circulation is a little over two and a half weeks. . . . The clearing-house figures just quoted contain a large number of 'butcher- baker' (second-hand) transactions, and these must be deducted in estimating circulation rates."*

*C. H. Douglas in “The New and the Old Economics”.

After making the necessary correction for the volume of second-hand transactions and for

payments that do not go through the clearing-house, we may conclude that the average period of circulation of the money spent upon consumable goods is about two months, or one-sixth

The effect of the very great disparity between these two rates is as follows:

Let N1 = 1 = number of circulations per year, say 6.

N1

Let N2 = 1 = number of circulations per year, say 1

N2 20

Let A = all disbursements by a manufacturer which create costs

= wages and salaries

Let B = all disbursements by a manufacturer which transfer costs

= payments to other organisations

The manufacturer pays £A per annum into the N1 system, and £B per annum into the N2n system

Disregarding profit, the price of production is £ (A + B) per annum.c But to purchase (i.e.to cancel the allocated cost of £(A + B)) there is present in the hands of the consumer :-

£(AN1 + BN2) = £ (A + B N2 )n

N1 N1

Consequently, the rate of production of price values exceeds the rate at which they can be cancelled by the purchasing power in the hands of the consumer by an amount proportional to

B (1 – N2 ) = approximately B

N1

Page 5

This defaicit may be made up by the export of goods on credit, by the writing down of goods in credit, by the writing down of goods below cost, by bankruptcies, and by money distributed for public works and charged to debt. But in the main it is represented by mounting debt.

It will readily be seen how this situation in which, not production, but money, is chronically insufficient, must transfer control to the institutions which have acquired the monopoly of money-making. In order that the industrial system may not grind to a standstill, an increasing issue of money, chiefly for capital production, is necessary to bridge the gap between purchasing power and prices – a gap which is the only possible explanation of the anomaly between a half-idle production system and a half-starving population. But as this fresh money is claimed by the banking system, and has to be repaid, the situation is cumulatively worsened.

While the question of War Debts is in essence only a special, if important, case of the generalised statement, it does in fact lend itself to conclusive demonstration of the defective accounting system we call Finance. Any realist will appreciate that a war is paid for (physically) as it is fought. The material, the guns, shells, aeroplanes are the result of work done and matter converted, and when used they are destroyed. Clearly an accounting system which implies (a) that an asset exists corresponding to the securities held in the form of War Bonds, and (b) that there is any physical process going on corresponding to “taxing the country to pay for the War,” must obviously be fallacious. If the taxes were applied to making exactly the same amount of material destroyed in the War, then the public would have both the war material and the taxes, in the form of saved wages.

Page 6